- This essay will inevitably contain spoilers!

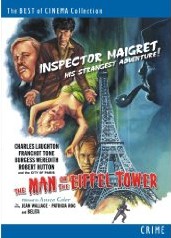

'THE MAN ON THE EIFFEL TOWER' (1949)

- A review by Richard Harrison (2010)

It is a peculiarity of the 21st Century movie star that they feel they

can diversify into other fields of artistry without, it seems, any

grasp that people aren’t always good at everything. Thus, it is not

uncommon now for actors to star in a few films, turn their hand to

directing and even make records. George Clooney, Kevin Costner, Ben

Affleck and Kiefer Sutherland are just four names who have made the

transition (or rather leap) to directing, Steven Seagal one name who

has branched out into music. Once this simply was not the case- actors

knew their place, and were humble enough to stick to doing what they

did best. Therefore, we can only surmise at what a Cary Grant directed

film would look like, or what the over-riding themes of Gary Cooper’s

films would be. Of course, as with most rules, there were exceptions.

Charles Laughton’s solitary venture behind the camera for Night of

the Hunter (1955) is now considered a triumph, though it was not

praised at the time. Burgess Meredith also took a brief turn behind the

camera (replacing Irving Allen, reputedly at Charles Laughton’s behest)

for The Man on the Eiffel Tower, an RKO curio from 1949.

Usually, a studio system film would not merit the “curio” tag, but The

Man

on

the

Eiffel Tower certainly does. Shot in ANSCO Colour (the

European equivalent of Technicolor), the film captures post-war Paris

in fascinating (if rather fragmentary) fashion. Indeed, the move out of

the studio backlot and onto the streets of Paris has an unusual effect,

and it is this, allied to the colour film stock, that gives The Man

on the Eiffel Tower a rather exotic aspect. (It is worth noting

that the importance of the city itself is recognised in the opening

credits- it is listed in a frame on its own along with the actors).

One of the other reasons the film is such an oddity is in its casting.

Inspector Maigret is played by the (miscast) Charles Laughton, who

strikes an uneasy balance between Henry VIII-style over-bearing-ness

and that of a bewildered bystander. Johann Radek is portrayed by

Franchot Tone (a mainstay of 1930s films but now, in his mid. 40s,

finding major film roles impossible to procure). The pair are ably

supported by Burgess Meredith (who should really have stayed in front

of the camera) and less ably by a range of other stars and starlets who

fight wooden dialogue and leaden direction with admirable- if futile-

spirit. Given this offbeat mix of cinematic ingredients, The Man on

the Eiffel Tower could have been something much, much better if it

were in the hands of an experienced director such as Hitchcock or

practically any of the émigrés who made such

atmospheric Noirs in the 1940s and 1950s.

Given its many shortcomings, should The Man on the Eiffel Tower

be valued? Surprisingly, my answer would be ‘yes’. Unlike many films

which have very little points of interest, this little film has

several- even if they are not particularly well executed. If nothing

else, the use of the (now faded) ANSCO colour process makes it a

necessary piece in the jigsaw in the technological development of

cinema, the rather bizarre performances combined with the unusual use

of location filming adding to the tapestry of a film which, thanks to

Odeon Entertainment, is freely available once again.

Odeon Entertainment website

Back

Home